One of my new clients is a “wordsmith.” She helps authors get their books into print and then promotes them. I have a lot of respect for her. Just recently, though, as I understand her situation, a new client of hers asked her to not only edit the text of his print book but also lay it out in MS Word. He wanted to save money by not paying a designer to lay out the text of the book (fortunately, he did pay for a professionally designed cover).

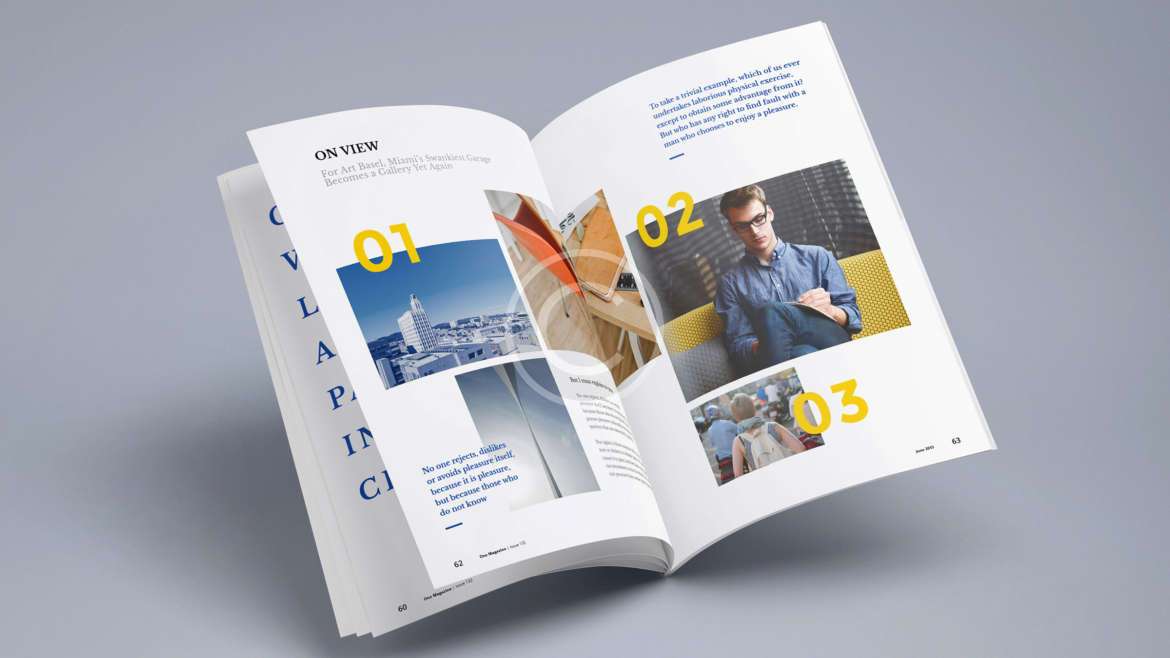

I want to clarify the direction in which my thoughts are going. My client referred to the text design of the print book as “desktopping.” This term, in itself, does not carry the weight of the skill and experience of the proper term, “book designer.” In fact, it is easy to assume that just because one can process the words of a print book, add photos, add a table of contents, and such, that this is of the same caliber as the product created by an experienced designer who understands typography, layout, page grids, the use of white space, and all the myriad of nuances that make a professionally designed book aesthetically appealing (and easier to read).

When I started in the field of publications management, back in the late 1970s, I would take the manuscripts for the magazine (I was the managing editor) to the typesetter. She produced galleys (a photographic process of setting each line of type on a dedicated computer). These were then physically pasted up on grid paper based on a mock-up of the design that I had created. (The key here is that the typesetter did nothing but set type. She was an expert in this aspect of publishing.)

Granted, this was before desktop publishing, which democratized publication design by making it “possible” for anyone to produce text. But the typesetter understood the various classifications of type, how the type letterforms differed, why to choose one over another, and how to “tweak” type with such precise controls as kerning and tracking. She also understood such elements of design as adding letterspacing (moving successive lines of type slightly apart to improve readability).

The designer who then pasted up the magazine also understood these elements of design. She knew exactly how to specify these type nuances and communicate directly with the typesetter such that both professionals could work together to create a readable, attractive magazine based on the paper mock-up I had taped together (using photocopies of the strips of typeset manuscript—the galleys). Everyone understood their own and everyone else’s job. Everyone could communicate based on this understanding. But since everyone’s respective job differed from everyone else’s and since each required a depth of knowledge not held by the others, it took all of the participants to produce a quality magazine.

Then, in the late 1980s, everything changed. At that point, everything could be done on a desktop computer. Granted, this made the publishing process faster, easier, and cheaper. Untrained staff could produce a newsletter for next to nothing. For certain things, that’s great. (I’m a great believer in doing what is necessary in a particular situation, neither more nor less. For certain publishing tasks, good enough is good enough. Most people won’t see the difference. When I started in the field, I couldn’t tell the difference.)

Back to My Client

I don’t want to disparage my client. I think she is wonderful and highly skilled. However, in order to help her prepare the text for her client’s print book (with me working as her commercial printing broker), I have had to teach her to look closely for a number of things. Catching and correcting these errors will make her client’s book look more professional and be easier to read. If you are new to design, these are some things you might want to consider as well, whenever you design a print book:

- My client set the entire book—excluding the cover–in MS Word rather than InDesign. Some printers won’t accept MS Word files. When processed in prepress, some MS Word files can apparently develop problems. I believe these include reflowing of copy and/or potential inadvertent font changes. This may have been addressed and corrected in the recent past, but I was always taught by printers to use InDesign or Quark. Typesetting functions of these dedicated page composition software packages are more nuanced and more precise. In my client’s case, she will save the MS Word file as a PDF (which should eliminate problems, or at least keep them from creating unexpected results). However, I have asked the printer to check the files carefully as well. When my client reviews the hard-copy proofs of the print book, she will also be able to look for any anomalies (changed fonts or reflowed copy). But if she had used InDesign, there would have been far less opportunity for error.

The Takeaway

Always use a dedicated page composition program for laying out your publication, brochure, or any other commercial printing job. Don’t use Microsoft Publisher. Don’t use Illustrator. Don’t use Photoshop. Use InDesign or Quark.

- My client set the text of the book justified, without hyphenation. Therefore, MS Word either jammed words together (with too little word-spacing) or put too few words on a line (sometimes only three words with large spaces in between). This minimizes readability, because the spaces between words are so different from line to line throughout the 428 pages of the book. And minimized readability tires the reader’s eyes, making it less likely that she or he will continue reading. Moreover, if the type looks amateurish, people will question the accuracy of the content. It’s like a bad proofreading job. If your manuscript has spelling errors or errors in grammar, the reader will wonder whether the facts in the print book are also incorrect. It’s human nature. In fact, it may not always even be conscious. And at best, it slows down the reader’s progress.

The Takeaway

Avoid justified text whenever possible. Flush left/ragged right text is easier to read because the space between words is always the same. The reader’s eye gets used to this, and she or he gets into a reading “rhythm,” proceeding more quickly through the text. If you have to justify copy, use hyphenation to minimize differences in word spacing. But also carefully review the text (on a printout, not the computer screen) to identify problematic lines of type (which create a condition known as “rivers of white” running down the page).

- My client left some subheads at the bottom of pages without the paragraphs to which they referred.

The Takeaway

Make separate review passes through the entire print book text, looking for a number of errors and inconsistencies: in hyphenation, spacing between lines of type and particularly between typographic elements such as bulleted items (anything where the spacing is different from that of the running text). Make sure there are no “widows” or “orphans” (parts of words at the beginning or end of pages). Leave subheads with at least a few lines of the following paragraph, and start a new page with at least a few lines of copy.

- My client kept all photos as RGB images in a book text file that was for a black-ink-only print job. While the digital printer will automatically convert these to grayscale (black and white halftones), some of my client’s images will become too dark in this transition. So I have asked her to change the mode from RGB to grayscale and re-import the images. This way she will see how she can expect the final printed images to look. If they are too dark, she can lighten them before sending the job to press.

The Takeaway

Never send a color job to press with RGB images. Images for print should be CMYK (if the book is full color). For black-ink-only text blocks, always use grayscale, not color or bitmapped, images.

- On the title page, my client did not kern the letter pair “Wa” (in the word “War”). In large type, pairs of letters such as “Wa”–or, worse, “WA”–will appear to be too far apart. In my client’s case, this looked amateurish because of the size of the type (the title of the book on the title page). The type size magnified the flaw.

The Takeaway

In your own work, print out a copy of the text, and look for too much space in the pairs of letters, particularly in larger type. Learn how to tighten type using the “kerning” function (again, something like this will be superior in InDesign and Quark because these applications are intended for typesetting).

Why Is This Important?

Everything you design, print, and distribute is an ad. It reflects the quality of your work. If your type design looks amateurish, this will make your reader question the accuracy of the content, at worst, or tire his/her eyes, at best.

What’s the Most Important Thing You Can Do to Avoid These Problems?

Study typography. Learn the difference between Old Style, Transitional, and Modern typeface classifications. Learn to kern type. Make the study of type an interesting, lifelong pursuit. Understand how typography fits into the overall design of a printed piece. Look at printed jobs you like and try to articulate why they are attractive. Expect your knowledge base to grow and expand, but assume this will take time. If you don’t have the time, hire a professional designer (not a “desktopper”), and then focus on what you yourself do best.